The Basics of Pooling and Servicing Agreements

To securitize a mortgage loan, the lender or its servicer must contribute mortgage loans into a trust and sell those loans to the trust pursuant to a pooling and servicing agreement (PSA). Mortgage-backed securities are then offered to investors by the investment banker from the trust formed by the PSA. For a thoroughly detailed description of the mortgage securitization process, see our blog Securitization 101: The Giant Sucking Sound.

A pooling and servicing agreement (PSA) details the relationship between the depositor, servicer, master servicer and trustee of the mortgage loan pool. The PSA also establishes the composition of the mortgage loan pool and the rights and duties of each party to the PSA, including when and how mortgage loan default events of default are dealt with by the servicer or master servicer but also how a foreclosure action is commenced in the name of the trustee and the procedure to be followed to secure the requisite subordination or assignment of third-party creditor liens or other encumbrances of title that should not exist to allow for the free and clear sale of the subject real property. The mortgage loan pool has a schedule listing the mortgage loans that are included in the mortgage loan pool. The PSA contains the representations and warranties of the parties to the mortgage loan pool at the time the mortgage loans are to be conveyed to the trustee. Because the loans are being sold to the PSA, the seller wants to ensure that the loans can be sold or more likely transferred to the trust. To accomplish this , the lender will take back a promise to repurchase or substitute one of the loans if certain disclosures are misstated or if representations and warranties made by the lender are incorrect. The lender will also want the buyer to disclose certain facts such as whether the loans are subject to a bankruptcy stay, whether there are any proceedings in bankruptcy or insolvency which could affect the enforceability of the mortgage loan documents, whether any borrower payment or monetary reserves are maintained in the mortgage loan file and whether any borrower holds security deposits, Medicare or Medicaid or other statutory liens which affect the enforceability or priority of the mortgages in the mortgage loan file. The PSA expressly states the seller’s responsibility to purchase the affected loans if certain disclosures are made or events occur. The PSA provides that upon a sale to the trust, the trustee will hold bare legal title to the subject real property and will execute upon foreclosure. The PSA may set forth the obligations of the servicer with respect to servicing and collecting mortgage loan payments. The PSA obligates the servicer to send borrowers a notice of default and grace period letter and a pre-foreclosure warning about the foreclosure process before servicing can foreclose. In fact, the PSA expressly states that the trustee will execute a notice of default and commence the foreclosure action by an attorney as a necessary step in the foreclosure process.

The PSA will often provide for multiple interpretations and will not agree to one understanding of how to deal with certain types of foreclosure related issues. Therefore, it is important to understand how to interpret the PSA prior to instituting or defending a foreclosure action.

Key Aspects of a PSA

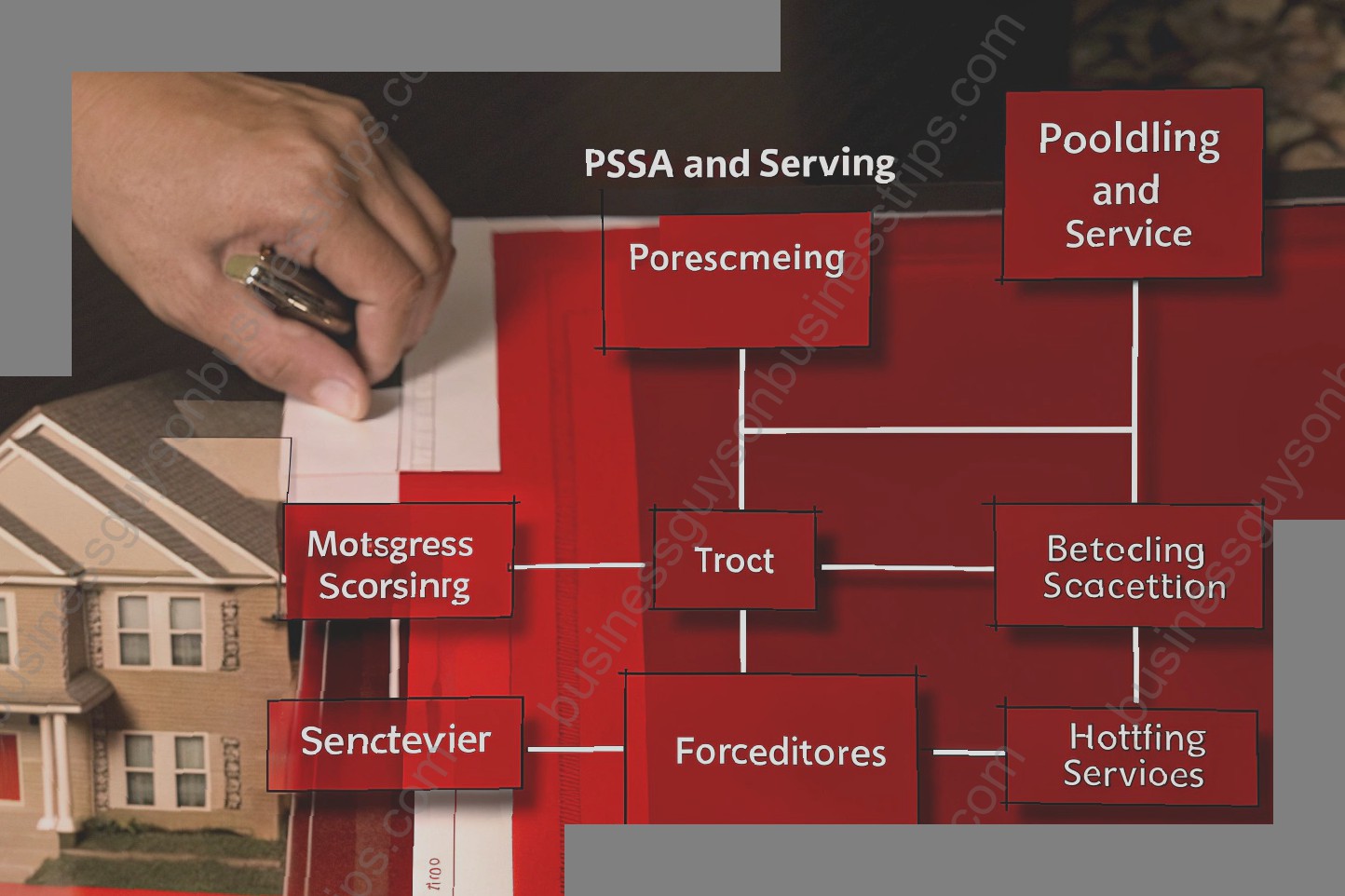

Given the multitude of securitized pools, the only way to know the terms of a pooling and servicing agreement ("PSA") is to carefully review the PSA for that particular pool. Each PSA is tailored to the underlying collateral and the parties involved, so while there may be some similarities, the material terms vary from pool to pool. With that caveat in mind, while the material terms may change, certain terms will be present in each PSA. The following graphic lists key components and terms of a PSA.

The lead servicer is often the issuer or an affiliate of the issuer that sells securities to investors. Servicers do not necessarily have to complete the loan. A lender/lender affiliate may complete the loan and either retain the servicing rights or transfer them to the servicer. Alternatively, multiple servicers may act on behalf of the issuer. The servicer may also delegate certain duties to sub-servicers. The seller is primarily responsible for selling the mortgage loans to the issuer. In some transactions, the seller is also the servicer. If the seller is also the servicer, the seller will be responsible for conveyance of the servicing file and carrying out the duties of the servicer outlined in the PSA. The seller may also be a lender, also known as the sponsor and is limited to securitization with its own or its affiliates’ mortgage loans (as stated in the PSA), as the sponsor must retain at least a five percent interest in the risk of the credit risk of the securitization. The custodian is responsible for the safekeeping of the mortgage loans and related data. The mortgage loan files are delivered to the custodian at the time of sale. The custodian reviews the loan files to determine if they are according to the terms of the PSA. If they are not, the custodian returns the files to the seller, and the seller has a cure period to remedy the defect. For sub-servicers, the servicer provides oversight by monitoring compliance of both the mortgage loans and the sub-servicer in accordance with the PSA. The sub-servicer assumes many of the day-to-day servicing responsibilities. Ideally, the sub-servicer prepares the monthly and annual servicing reports, collects payments and remits to the trustee. The sub-servicer may also receive fees from the trustee. Sub-servicers are reimbursed by the servicer for certain expenses that they incur when operating under a PSA. In addition, the PSA also sets forth the requirements for the servicer to maintain the possession of the mortgage files. The PSA also requires that the servicer notify the issuer of certain events such as delinquencies and defaults.

Searching for Pooling and Servicing Agreements

There are several ways to search for pooling and servicing agreements, although each method depends on the nature of the agreement that I have been asked to review. This list highlights some of the ways to search for PSAs but does not include every source. We also tailor our search based on particular clients/transactions so this is not a comprehensive list.

The SEC’s EDGAR database is one of the best search tools for PSAs as nearly all PSAs for public securities offerings are filed through the EDGAR system. Under the EDGAR search category "Company Filings", select "Search by filing type" and use the following search parameters: In the "Filing Type" field, enter 8-K or 424B5 (for prospectuses), leaving the date fields blank. In the "Company or Fund Name" field, enter a part of the serving institution’s name. For example, if Wells Fargo is the servicer, you may search "Wells" and "Bank" as Search Terms and that will give you the results you need. The results of the search will take you to the first page in the filing; you may have to scroll down to find the PSA.

Another good source for PSAs is Intex. The PSAs on the Intex platform are typically very clean and easy to work with, so it is a good place to start. It is important to note that Intex does not have PSAs for large governmental issuers.

For PSAs originally entered into in prior to the adoption of e-Servicing for RMBS by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation into its new business rules earlier this year, you may request hard copies from the Transfer Agent or Ginnie Mae Issuer as these documents still exist in paper format. Please note that response times are typically 60-90 days!

As a last resort, PSAs are searchable through the Vault. Simply hover over the word "search" at the top of the home page and click on the word "Vault." The Vault is a valuable tool for any securitization lawyer, analyst or researcher.

The types of searches can be performed are listed to the left of the webpage for easy navigation. Select the "Search" tab in the Vault and then select "Mortgage Loan Data", "Disclosure Documents" or "Securitization Documents" as your jurisdiction. For example, in the "Disclosure Documents" field, you may search by the CUSIP, pooling and servicing agreement, note date or issuer.

Common Issues When Seeking PSAs

For many parties getting involved in a reference pool, whether it be investors, servicers or even broker-dealers, one of the first things that is needed is a copy of the applicable pooling and servicing agreement ("PSA"). Unfortunately, other than the investor special servicer, servicer, or trustee, most of the industry does not have easy access to the PSAs. Further complicating the PSA search is the fact that many entities, such as rating agencies and servicers, do not want to give copies of the PSA any more than is necessary.

In some cases, the Trustee for a deal will have a public website where you can register to get a copy of a PSA . However, in most cases, PSA copies have to be requested from the servicer. For rating agency reasons, sometimes the PSA can only be provided to the initial purchaser of the deal (generally the initial MBIA insureds). None of these methods is very convenient and in many cases it takes a substantial amount of time just to get the PSA provided at all.

In addition, in many cases the PSA is produced in a format that makes searching the document for certain provisions or definitions very difficult. Not only are most PSA’s scanned images that are not text searchable, but also many of the PSA’s include Series Supplements that add an additional level of confusion.

PSA Legal Analysis

PSAs are generally not given as much attention as a mortgage loan document would get, and are often overlooked, or at best, skimmed over. But the PSA is the centerpiece of a securitization, and failure to focus on its details can have significant, albeit sometimes subtle, consequences. A PSA lays out the complete structure of the securitization and often contains the terms of the deal that might not otherwise be documented anywhere else, because the parties agreed to some terms "off-market" or otherwise on a special, one-off basis. For example, it is not unusual for servicers or master servicers to negotiate terms that are contrary to the usual form, such as subservicing agreements that have no deductible cap, or even unlimited liabilities, or servicing agreements where the servicer will advance all or a high number of the advances without reimbursement.

For that and other reasons, PSAs should be reviewed carefully for proper scope of authority and to ensure that the consent and consultation rights for a master servicer, trustee or other party are not unduly restricted or the scope of the delegation is otherwise not properly documented. For example, it is critical that the PSA expressly reserves the rights to consent or consult in instances where the PSA does not contain any specific right to terminate or control the day to day business of the servicer. There have been several instances where litigation arose over such questions, such as Bayerische Landesbank v. Lehman Bros. Mortgage Capital Inc., 650 F. Supp. 2d 253 (S.D.N.Y. 2009), aff’d, 416 F. App’x 69 (2d Cir. 2011). In that case, however, the right to approve servicers was found, because the PSA also contained a detailed procedure to approve or reject a proposed servicer, but in other cases, such language was found not to support that proposition.

And, as previously mentioned, the PSA is the one document that can be used to illuminate the intent of the parties to the transaction, so if something goes wrong with a securitization and there are no specific agreements or other writings that state the parties’ intended approach to resolving the dispute, the PSA should be consulted. As one court put it, "the P&SA does not govern the entire relationship between the parties, but it does describe their relationship vis-a- vis the 20% interest in the Collateral they acquired." LB CDO 2007-1 Ltd. v. Credit Suisse Sec. (USA) LLC, 310 F. Supp. 3d 721, 726 (S.D.N.Y. 2018). The terms of a PSA are critical to an understanding of the risks and economic exposures involved in the securitization and can be of utmost importance in later disputes over whether of not a certain party was entitled to exercise discretion, such as to care for the collateral, to exercise remedies, and to the extent such discretion resulted in financial damages or liability.

To prevent or hedge against these disputes, and to provide certainty, PSAs may include detailed provisions regarding the rights of parties to commence an enforcement proceeding (see, for example, Oakwood Asset v. Bank of the Americas, 890 A.2d 1, 10-11 (Del. 2006)), including the requirement to obtain payment direction as a condition precedent to commencing suit, but if there are multiple parties with competing interests to protect, or if multiple events or conditions must be met before a party can proceed to commence a suit, there is still a chance for an argument to be made over whether the right to enforce the PSA was properly exercised.

Again, given the fact that PSAs set forth the rights of the parties, and the different tiers of parties to an securitization (master servicer, servicer, trustee, etc.) and their relative rights that are sometimes not inherent in the underlying transactions, the PSA is the most important document to review in case of a dispute to understand how the securitization was structured to function and how a particular party was expected to exercise its rights.

Recent Pooling and Servicing Agreement Trends

There are a number of recent trends in the area of pooling and servicing agreements (PSAs) that every lawyer in this space should be tracking. First, and most notably, with the announcement of the end of Active Financial Disclosure Simulation (AFS), issuers will no longer provide the initial PSAs so that practitioners cannot rely on information made publicly available concerning PSAs that have already been prepared. Of course, the PSA is now an addendum to the SEC Form 8-K under Regulation AB. In addition thereto , issuers are no longer required to provide the Regulation AB compliance statement that was formerly set forth in the PSA. Issuers are removing all references to Regulation AB compliance. Further, some investors are increasing the complexity necessary to perform their due diligence – that is, new, strange requests seem to be appearing. For example, with respect to tax loans and tax delinquency notices (TDN)? Why do new originators not want tax loans included in the pool? New originators are more often finding it more difficult to alter the servicing fee schedule or to amend PSAs to permit wind-downs. As ever, being a frequent user of PSAs will only make you better at negotiating PSAs.